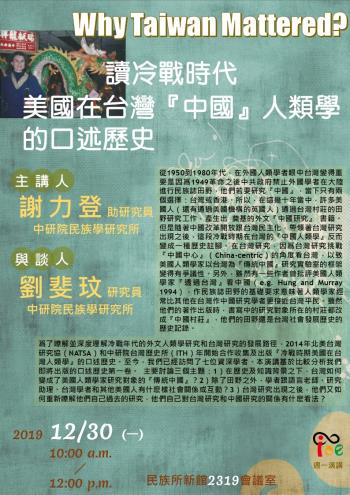

Why Taiwan Mattered? 讀冷戰時代美國在台灣『中國』人類學的口述歷史

|

||||||||||||||

從1950到1980年代,在外國人類學者眼中台灣變得重要是因爲1949革命之後中共政府禁止外國學者在大陸進行民族誌田野,他們若要研究『中國』,當下只有兩個選擇:台灣或香港。所以,在這幾十年當中,許多美國人(還有通過美國機構的英國人),如武雅士、葛瑞黛、王斯福、葛希芝、芮馬丁、郝瑞、沙學漢和其他人,通過台灣村莊的田野研究工作,產生出 奠基的外文『中國研究』 書籍。因此,可以說台灣在美國『中國人類學』的發展中扮演了核心的作用。但是隨著中國改革開放跟台灣民主化,帶領著台灣研究出現之後,這段冷戰時期在台灣的『中國人類學』反而變成一種歷史註腳。在中國研究中,許多研究中國的學者因為年輕時在台灣的初步田野調查,已經變成他們中國研究部分的序幕。而在台灣研究,因爲台灣研究挑戰『中國中心』(China-centric)的角度看台灣,以致美國人類學家以台灣為『傳統中國』研究實驗室的框架變得有爭議性。另外,雖然有一些作者曾批評美國人類學家『透過台灣』看中國(e.g. Hung and Murray 1994),作民族誌田野的基礎要求意味著人類學家經常比其他在台灣作中國研究學者更接近台灣平民。雖然他們的著作出版時,書寫中的研究對象所在的村莊都改成『中國村莊』,他們的田野還是台灣社會發展歷史的歷史記錄。爲了瞭解並深度理解冷戰年代的外文人類學研究和台灣研究的發展路徑,2014年北美台灣研究協(NATSA)和中研院台灣歷史所(ITH)年開始合作收集及出版『冷戰時期美國在台灣人類學』的口述歷史。至今,我們已經訪問了七位資深學者。本演講基於比較分析我們即將出版的口述歷史第一卷。主要討論三個主題:1)在歷史及知識背景之下,台灣如何變成了美國人類學家研究對象的『中國』。有什麽機構勢力或論述結構將戰後快速發展的台灣變成研究中『傳統中國』的田野地點?研究『中國』的美國和英國人類學家是如何看待台灣?2)人類學家怎麽做田野?除了田野之外,學者在台灣發展出什麽樣的社會關係?他們跟語言老師、研究助理、台灣學者和其他美國人有什麽樣社會關係或互動?3)台灣對人類學家的學術發展有什麽印象?中國開放之後,學者又怎麽決定離開或留在台灣?而在台灣研究出現之後,他們又如何重新瞭解他們自己過去的研究,他們自己對台灣研究和中國研究的關係有什麽看法?

Between the 1950s and the 1980s, the easy answer to “why Taiwan mattered” for foreign anthropologists was their inability to conduct fieldwork in (mainland) China after the 1949 revolution. For several decades, anthropologists like Arthur and Margery Wolf, Bernard and Rita Gallin, Myron Cohen, Stephan Feuchtwang, Hill Gates, Emily Ahern, Stevan Harrell, David Schak and others produced pioneering work in China Studies based on ethnographic fieldwork conducted within a relatively small archipelago of Taiwanese villages. Cold War American anthropology Taiwan played a central role in the development of the American anthropology of China. Following the opening of China, democratization in Taiwan, and the emergence of Taiwan Studies, however, this period of scholarship has become something of an awkward footnote. In China Studies, Taiwan’s status as the first fieldwork site of many anthropologists has become a small prologue. In Taiwan Studies, Taiwan’s historical status as a fieldsite for studying “traditional China” is controversial because it represents precisely the China-centric paradigm Taiwan Studies sought to challenge. However, although some polemical accounts have accused foreign anthropologists of merely “looking through Taiwan” to see China (e.g. Hung and Murray 1994), doing ethnographic work meant that anthropologists were often closer to ordinary people in Taiwan than other Sinologists. Even though the villages they researched became timeless “Chinese villages” in their publications, the accounts they produced are nonetheless historical records of Taiwan’s social development. In order to better understand this period of scholarship and its relationship to the development of Taiwan Studies, the North American Taiwan Studies Association (NATSA), in collaboration with the Institute of Taiwan History (ITH), has since 2014 been conducting an oral history project interviewing this generation of scholars. In this talk, based on a comparative analysis of the oral histories appearing in a forthcoming book, I examine several key themes. 1) How was Taiwan constructed as a fieldsite? Specifically, what kinds of institutional forces and conceptual frameworks facilitated a changing Taiwan’s suitability as a site for studying “traditional China”? How did foreign anthropologists themselves see Taiwan in relation to their research interests in China? 2) How did anthropologists conduct fieldwork? Specifically, what kinds of social relationships and embeddedness in Taiwan existed beyond their fieldsites? What kinds of relationships did anthropologists have with language teachers, research assistants, Taiwanese academics, and other Americans? 3) What role has Taiwan played in their subsequent academic careers? Specifically, following the opening of China, why did anthropologists choose to either leave or stay in Taiwan? Following the emergence of Taiwan studies, how do anthropologists of the earlier generation themselves understand their own research in relation to Taiwan Studies and China Studies today?